The annual Omnivore Food Festival, held from February 11-13 in Deauville is held before an audience of more than 1 000 food professionals and enthusiasts each year.

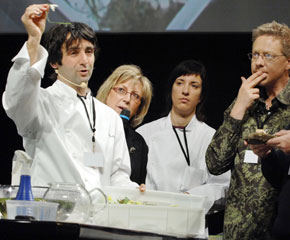

The 30 chefs who came from the farthest reaches of France and around the world to demonstrate their avant-garde cooking styles showed that even as techniques become more international, chefs are increasingly attached to their roots.

One of the most striking demonstrations was by Danish chef Rene Redzepi, who draws his inspiration from the earth where his vegetables grow.

Because this sandy soil near the sea contains crushed shells, he coats vegetables in a butter and shellfish emulsion just before serving them.

“Terroir” – which literally means the land – is not a new idea for the French, who have long celebrated the natural riches of their regions. But, in a new climate of cross-pollination among cooks from around the world, French chefs are no longer afraid to borrow ingredients from elsewhere to better illustrate what is close to home.

A perfect example is Gerald Passedat of “Le Petit Nice” in Marseille, who added hibiscus flowers to a long-cooked lobster consomme to create an eerie blue colour reminiscent of the depths of the Mediterranean.

Overlapping strips of carrot and red endive recreated the “shell” on the lobster tail. “Blue is a colour that people instinctively shy away from in food,” he said, “but once people taste the sauce I think they get past that.”

No chef got through a demonstration at the Omnivore food fest without using modern appliances such as the Thermomix (which heats and mixes at the same time), the Pacojet (which transforms frozen ingredients into ice cream or powder), or the steam oven. Only rarely, though, did modern technology seem to get in the way of good food.

One of the most innovative chefs at the festival was Seiji Yamamoto from the restaurant “Ryugin” in Tokyo, who used edible “ink” to print patterns on his plates that complemented each dish. “I try to make the most of the techniques available,” he says, “but before I send a plate to the client I always ask myself, ‘is this Japanese food?'”. If the answer is no, I won’t serve it.

Like many Japanese chefs, Yamamoto made a pilgrimage to France early in his career to learn haute cuisine techniques. He now benefits from opening his kitchen to cooks from around the world.

Sebastien Bras, who works closely with his father Michel Bras at their celebrated restaurant in Laguiole and helped set up its twin in Japan, summed up the new spirit on display at this festival.

“Each of us here is revealing his secret garden. It’s about a love of the craft, a love of terroir and each chef’s personal experiences. Technique should always take a back seat to pleasure. If the technique dominates, then we are doing something wrong.”